Open Letter to the Slave Voyages Project

Excerpt of an interview of a formerly enslaved woman named Anna King, c. 1933. This was the inspiration behind the name Oceans of Kinfolk.

To the members of the Slave Voyages Operational Committee, Steering Committee, and all other relevant parties:

This time of year a full decade ago, I was waiting tables in Washington, D.C., but between shifts, I would often find a secluded table in the restaurant, pull out my laptop, and work on the thirteen applications I would soon submit to various doctoral programs in history. Thirteen was a lot, I knew, but because I didn’t yet have a master’s degree, I was worried I wouldn’t get in anywhere unless I cast a very wide net. And I very much wanted to get in somewhere (maybe anywhere), you see, because I had made up my mind that I was going to study the history of race and slavery in the United States. Crafting those applications, I could not offer a clear statement about what it was, exactly, that I intended to research, but I do recall having precise clarity about my motivations for applying: as a white woman descended, at least in part, from enslavers, I felt an ethical and moral responsibility to contribute to work reckoning with the history of racial injustice in the United States. It was one thing to inherit such a bloody legacy, I figured, but quite another to willfully look away from it.

“I want to study the history of slavery in the American South because seeking complicated but whole truths about the people and places from which I come is now an instinctive impulse. It is, perhaps, an outward manifestation of my compulsion for introspection: surely a natural byproduct of being raised by two liberal-minded psychologists in East Tennessee.”

-- Excerpt of the author’s “personal statement” included in applications to doctoral programs, 2014.

Fortunately, my fears about not getting in anywhere proved unfounded, and I ultimately enrolled at Johns Hopkins University. Once I was there, my scholarly interests slowly came into view. This was 2015, a time when historians of American slavery were quite fixated (although not for the first time) on the relationship between slavery and capitalism. Some of the resulting literature—“new economic histories” of slavery—resonated with my interests, but rarely through traditional economic analysis. Instead, I was most impacted by narratives connecting the histories of slavery and capitalism with the lived experiences of enslaved people themselves: works including Walter Johnson’s Soul by Soul, Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told and Daina Ramey Berry’s The Price for Their Pound of Flesh, for example.

In terms of method, though, I developed a deep admiration for many works from an earlier period: tombs mostly written in the last half of the twentieth century by social and labor historians. But it was not necessarily the arguments I found so impressive about these works. It was the sheer amount of research they represented: years, sometimes decades, of archival immersion. Whether we call that kind of research “cliometrics” or “data,” my point is the same, and you’ll find it in the extensive footnotes and bibliographies of The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom (Gutman), or Life in Black and White (Stevenson), or Slave Counterpoint (Morgan), or Many Thousands Gone (Berlin), or The Slave Community (Blassingame), or…the list goes on.

But when it came to narrative intent and subject matter, I found the greatest inspiration in works concerned with family, kinship, and belonging among enslaved African Americans, and the centrality of these themes in fugitivity and other forms of resistance. Most, although not all, of these studies were written by Black feminist historians, although some did not or would not identify as such. At the time, these works included Stephanie Camp’s Closer to Freedom, Tera Hunter’s Bound in Wedlock, and Heather Andrea Williams’s Help Me to Find My People, for example.

As any graduate student in history knows, however, it is one thing to have intellectual interests and ambitions, but quite another to find sources suited to both. As for me, the truth is that I got lucky, very lucky. Someone told me where to look. After some seminar or another (I can’t remember which) during my first semester at JHU, a professor I did not yet know suggested that I might want to check out a collection of newly digitized records. So, once I got back to my apartment, I did as I was told. I logged into the university library’s website, and from there, clicked through to a site called Slavery & Anti-Slavery: A Transnational Archive. And that is where I found the them: “Inward Slave Manifests filed at New Orleans.”

The very first link I clicked on within the collection literally took my breath away. It contained an entire reel of digitized microfilm: more than 500 images of ship manifests, many of them several pages long. But the manifests didn’t list cargo. They listed people, enslaved men, women, and children. How many of these documents are there? I wondered. How many people? Hundreds? (No.) Thousands? (No.) Tens of thousands? (Yes, I would eventually realize, tens of thousands.) I was only just beginning to understand what these records represented, but even then, I was overwhelmed by the emotional weight of them. So many names. So many loved ones. So many ancestors—not mine, no, but someone’s. Many someones.

The names on those records, I soon understood, belonged to individuals who had been trafficked to New Orleans from ports up and down the Atlantic coastline, mostly in the forty years before the Civil War. With this realization, I thought of my own family. I thought especially about my grandfather Fletcher, and the stories he had told me about the people who raised him, his grandparents, both of whom were born well before slavery’s end. In fact, as a little boy, my grandfather’s grandfather witnessed the lynching of his father (my grandfather’s great-grandfather): retribution for having fought for the Union and against slavery and then having the audacity to return home to East Tennessee alive. I thought about how I knew this story, about how I know many of my people’s stories, how I carry them with me.

So to whom did the people on these manifests belong? Not as property—the documents themselves answered that—but as kin? Who was carrying their stories? Did those people know about this story? Did they know about these names?

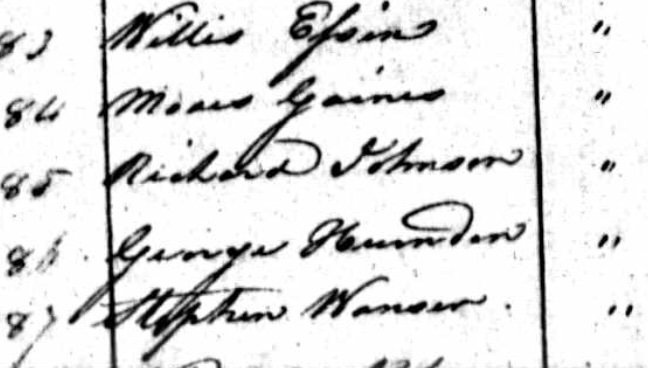

Manifest of the Virginia, sailing from Baltimore to New Orleans, January 1826.

In retrospect, I puzzle over my own confidence (arrogance, maybe) back in 2015, when I decided to build a dataset of these records. I had no training in data entry to speak of, much less any knowledge of database design. I could not have defined “relational data” if my life depended on it. Undeterred, apparently, I opened up Excel (my first mistake, as you know), and got to work.

It was clear from the beginning that the majority of the antebellum coastwise traffic carried enslaved captives to New Orleans, the nation’s largest market for buying and selling human beings. It was also evident that most of the trafficked individuals came from Virginia or Maryland. So, given my place of residence at the time, I decided to focus, at least for my first year paper (a rite of passage at JHU), on the traffic of enslaved persons from Baltimore to New Orleans, a population I would eventually discover to include 12,300 men, women, and children. Understandably, my two advisors tried their best to persuade me that my goal of to building a comprehensive dataset of this traffic—essentially a subset of the larger traffic to New Orleans—was unrealistic. Instead, they said, I should “sample,” meaning transcribe only a select portion of the manifests of voyages from Baltimore to New Orleans. I told them I would consider their advice, but in truth, I had already dismissed it.

By winter break, I had completed data entry, and the following spring, that of 2016, I presented my first year paper, Trouble the Water: The Baltimore to New Orleans Coastwise Slave Trade, 1820-1860, a study based largely although not exclusively on my analysis of the dataset I had produced. My aunts and uncles drove up from D.C. for the event, but aside from their presence in the seminar room, I remember just one part of my first year paper defense: the moment when someone asked if I intended to focus on the same history for my dissertation. I answered in the affirmative but with a caveat: I would be expanding my study to encompass the entire coastwise traffic of enslaved persons to New Orleans.

This, of course, meant I had a great deal more data entry to do. While it would be several more years before I would be able to do this math, the traffic of enslaved persons from Baltimore represented less than a fifth of the total coastwise traffic to New Orleans. I decided I would take it one port at a time: complete data entry for Norfolk, VA, for example, then Richmond, then Alexandria, and so on and so forth until there were no manifests left to transcribe. At my advisors’ insistence, I applied to the university library for funds to support two undergraduate researchers to help. Then I typed up a nine-page guide to data entry. The undergraduates I ultimately selected to work on the project were extremely bright, and I am sure they did their best with the records I assigned them (manifests from Charleston and Mobile to New Orleans, which collectively listed about 10,000 enslaved persons). Through no fault of theirs, however, they would have needed a great deal more practice deciphering nineteenth century manuscripts to be able to do the work in a way that I wouldn’t feel obligated to replicate myself. So, once I had finished all the manifests from the Upper South (documents listing approximately 53,000 individuals), I redid many of the Mobile and Charleston manifests. All in all, building a dataset of the coastwise traffic took a full five years.

Five years, not coincidentally, was also the amount of time allotted to me by Johns Hopkins to complete my doctoral studies on their dime. For this reason, there was never a time in which I could fully focus on data entry. It had to get done, but so did the rest of my research, not to mention my coursework and preparation (reading) for comprehensive exams. Just to be clear, though, I did this to myself. I had and have no right complain about my workload, and the truth is, I wouldn’t have complained anyway. The work—especially the data entry—felt meaningful, important, even. I just wanted to get the information from these records online, the names especially, and I promised myself I would find a way to do that if I could only find a way to finish it all.

I don’t often talk about the work that went into building the dataset that eventually became Oceans of Kinfolk. I have described, both in talks and in writing, the steps I followed, but I have never explained the labor that went into it. For reasons that will become clear, however, I think it is appropriate that I do so here.

Between August of 2015 and December of 2020, I generally worked about fourteen hours each day, sometimes more. There was variation from one day to the next, but in general, data entry took up roughly half of my working time. Looking back, I regret that I did not find some way to acquire one of those expensive office chairs that swivel around and have cushions, but I didn’t. Instead, I sat in a wooden folding chair. It was from Target and it was cheap, but I paid dearly for it in more ways than one. Predictably, I developed severe pain in my back and left hip. I had broken the latter in high school, but it hadn’t bothered me for years at that point. Running daily helped my back and it no longer bothers me, but the hip pain lingers still. Then there was the ordeal of a catastrophically broken arm, something I should acknowledge was my own damn fault.(One day, in preparation for hosting a dinner party, I decided to stand on the aforementioned chair to hang a piece of art. I don’t know what I expected to happen, but yes, the folding chair folded and I came crashing down. I will spare you the details, but the resulting injury meant I could neither bend my left arm nor feel most of the fingers on my left hand for approximately a year of the process I am about to describe.)

I got extremely tired of people asking what happened to my arm, or—worse—how I would be able to finish data entry, much less my dissertation, on time, so I usually tried to cover it up as best I could.

Initially, I anticipated that data entry would be lot of work, but relatively straight forward in nature, simple even. There was even a time I thought I could listen to podcasts while entering information from manifests into my spreadsheet. I quickly learned otherwise. Manifests, I discovered, were extremely complicated sources. It was so easy to lose my place in a document listing 200 or 300 people. I typically worked through each manifest by transcribing first, all the names, second, all the genders, third, all the heights, and so on. This was the best method as far as I could tell, but it certainly wasn’t foolproof. A single mistake meant misaligning all the information for the entire document, so that the ages, genders, heights, and racial descriptors were all mixed up and attached to the wrong people. How was someone supposed to identify their great-great-great-grandmother if she was 22 at the time of the voyage but I had mismatched my columns and rows and thus listed her age as “0” (infant)? Worrying about this possibility, I double-checked everything, always. Of course, I knew there would be mistakes anyway.

To make things even more complicated, I wasn’t just consulting manifests. Any time I found the smallest bit of information about someone listed in my dataset—maybe they were advertised as a fugitive at one point and I had located that record, or maybe I was able to find a bill of sale from before or after the voyage, etc.—I integrated the information from the relevant record into my spreadsheet. How else would I keep track of what I knew about each person? Even then, at the very beginning, I sensed that I would one day be accountable for this work: accountable to people whose ancestors I was methodically adding to my spreadsheet, one name after the other. Unless I kept meticulous records of what I knew about each and every person, I worried, I might wind up having to say something like, “You know, I think I saw another record about your ancestor, but I’m so sorry, I can’t find it, and I can’t be sure…” I never wanted to say something like that. So, every time I found a new source, I found a way to represent both the document itself and the information it contained in my dataset. And so the spreadsheet grew, and grew, and grew, until eventually, it contained 162 fields. Thousands and thousands of records (rows, meaning names, meaning people), and for each person, 162 columns. Of course, I never was able to fill out all 162 fields for any one individual. But they were there just in case.

I could share dozens more examples of the complexity of this data, but to be honest, even the thought of doing that is giving me anxiety. You see, as I will explain later, I’m still wrestling with these documents now, a decade after I first encountered them. Before I get to the present, though, I have to go even further back in time, because I want to explain to you what it felt like to build this dataset.

When I was in second grade, I came home with a special assignment from school. I was supposed to draw my family tree. With my mom’s help, sketching her side of the tree was easy enough; its branches stretched all the way back to the 18th century. When I asked my dad about his side of the family, though, he had significantly less information to share. The reason, he explained, was that much of his extended family, my extended family, had died in the Holocaust. Besides, even before then, my dad said, his grandparents had lost contact with most of the family back in Eastern Europe (Poland, mostly) after immigrating to New York City to escape persecution.

Beginning that afternoon, I read every book I could find—children’s books as well as books from my parents’ shelves, unbeknownst to them—about the Holocaust. I vividly remember sitting at my desk in school and wondering why everyone didn’t talk about the Holocaust all the time. Why was my teacher talking about pilgrims? About multiplication? About the solar system? Didn’t she know what had happened? How were we supposed to prevent something like that from ever happening again if we weren’t even talking about it? Was I just supposed to pretend I didn’t know what had happened to my family? Several times a week, I would have nightmares that my parents and siblings and I were hiding from the Nazis in a bunker carved out beneath the sand at the beach we visited every summer on the South Carolina shore. I always woke up just as the storm troopers came to haul us away: the moment when I could see just their black boots descending the stairs to our secret hideout.

The manifests—the data, the names, the stories—hit me the same way. The work felt urgent. And no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t do it the way I wanted to. There were some names I simply could not make out. Many, many, names I could not make out. What was worse, I wondered, to guess or to not guess? Even when I took breaks, did other things, visited with family, went for a run, my mind went back to the names, the stories, the data. I talked about it all endlessly. I am sure I was insufferable. To be honest, I don’t think I’m any better about this now.

In 2018, the place where my little brother worked upgraded their technology and gave the old stuff to employees. My brother was kind enough to claim a monitor for me and ship it from NYC to my apartment in Baltimore. From then on, I had the benefit of two screens for data entry. It made a huge difference.

My grandfather, Fletcher Thompson, was always very supportive of my work. He read everything I wrote, as well as the many related books I mailed to him. Excel was beyond his technological ability, so he asked me to explain the dataset to him in person. The first question he asked was whether I had been able to find any information about the families of the people trafficked to New Orleans. “Sometimes,” I told him.

By the beginning of 2020, my dataset was complete (or at least I thought it was). In total, it contained information about more than 3,000 voyages, and the names of more than 63,000 enslaved men, women, and children who were trafficked to New Orleans in domestic vessels between 1820 and the Civil War: a magnitude that came into view ever…so…slowly.

Now, I am writing, in part, because I don’t think you understand what this data represents. Not fully, at least. And that’s okay; I am still grappling with it myself. But please, allow me to share what I have come to understand thus far, and how I came to understand it.

For me, the genealogical utility of the manifests was clear before anything else. This explains in part why I was so fixated, from the beginning, on making the information from those records—the names above all—accessible online. Of course, it’s not that I thought human trafficking was rare in the antebellum United States. On the contrary, I knew, like you, that between 1820 and 1860, more than a million enslaved persons were trafficked from the Upper South to the Lower South, mostly by professional traders. The great majority of that population, however, was trafficked over land: forced to march for hundreds and hundreds of miles on foot. Compounding this violence–the physical barbarity of the domestic slave trade–is the fact that there is no comprehensive record of the overland trade. Enslavers were not required to keep or file records about the hundreds of thousands of people they marched from one region of the country to another, and so they did not. Those names–like the names of the ancestors who survived the Middle Passage and those who did not–are lost forever.

But the coastwise trade was different.

After 1808, federal law actually required captains of coastwise vessels with enslaved persons onboard to file manifests listing those individuals by name at the ports of departure and arrival. The intention behind this law was to prevent the introduction of additional enslaved people from Africa to the United States, but the Act had a second result: the coastwise traffic of enslaved people was systematically documented.

But what I now know is that it wasn’t just the presence of the names on manifests that made them exceptional. It was their meaning, both now and when they were spoken there, in front of enslavers and customs officials. What I am trying to tell you is this:

Each and every one of those names was and is still a testimony of relational identity, of kinship.

This, though, was something that took a great deal of time and additional research to figure out. As a side project, I compiled a dataset of more than 11,000 fugitives from slavery who appeared in advertisements in Maryland newspapers between the 1740s and the Civil War. The differences between the names in this dataset–the fugitive dataset–and the names I had seen on manifests were striking. By comparing the names on manifests of voyages from Baltimore to New Orleans between 1820 and 1860, for instance, with the names of fugitives from slavery advertised in Maryland newspapers during the same period, I discovered that manifests were far more likely than fugitive ads to include full (first and last) names than fugitive advertisements. Curious whether this would be true for records from Virginia as well, I also compared the names on manifests of voyages from various ports in Virginia to New Orleans between 1820 and 1860 with approximately 6,00 fugitive advertisements published in Virginia papers in the same decades. The results were clear and consistent with my analysis of Maryland records; last names were way more common on manifests than on fugitive advertisements (as well as every other type of record I could find).

Curiously, I also found that formal names (e.g. “Michael” instead of “Mike”) were more common on manifests than on other records from slavery. For example, the name “William” plus its diminutive iterations (“Will,” “Bill,” and “Billy”) accounted for exactly the same proportion (6.8 percent) among male fugitives advertised in Maryland as it did among men and boys listed on manifests of vessels sailing from Baltimore to New Orleans. However, in fugitive ads, Will, Bill, and Billy were more common than “William.” On manifests, however, there were many more “William”s than all the Wills, Bills, and Billies combined.

So what explains these differences? Why were names on manifests from the Upper South more likely to feature formal names and surnames than the names on other records from slavery from the same region?

The answer is that enslavers authored fugitive advertisements and most other records from slavery, but manifests were drawn up by customs officials in consultation with the enslaved themselves. Here is how it worked: before they were forced aboard the vessels that would carry them to New Orleans, enslaved people were always presented by their enslavers to customs officials for physical inspection (let’s see how tall you are… hmmm…I’d call you “light mulatto”...say, you’re about 20?...and so on). But customs officials didn’t just inspect the captives; they also asked them a question: What is your name? And time and time again, the enslaved people before them answered fully and completely: My name is Moses Sweden Jr. My name is Charity Hall. My name is Simon Wilson. My name is…

Clearly, enslaved people in the Upper South placed a great deal of meaning in their names, especially their last names, and of course, plenty of other sources confirm this. But why were surnames inscribed with dignity? Why did they matter so much to enslaved people from Virginia and Maryland? I solved this riddle by investigating another:

Why was it that on manifests from the Upper South, more than half of all captives are identified by both first and last name, but on manifests from the Lower South (Charleston, Savannah, Mobile various ports in Florida and Texas, etc.), ninety-eight percent of captives are identified by first name only?

Manifest of the Ship States, sailing from Baltimore to New Orleans, April 1828. Note the surnames of the captives.

Manifest of the Sloop Jay, sailing from Charleston to New Orleans, February 1820. Note the absence of last names.

Here is a hint: the frequency of surnames was not the only difference between the names on manifests from the Upper South and those on manifests from the Lower South. Day names and place names—both of which were common in West Africa—were extremely rare on manifests drafted in Virginia and Maryland. Fewer than 100 enslaved people–less than a tenth of one percent–trafficked from the Chesapeake to New Orleans claimed day names like “Cuffy” (derived from “Kofi,” the Akan word for someone born on a Friday), “Juba” (an Ashanti word for someone born on a Monday), “Friday,” “Monday,” “Christmas,” or “Easter.” While still not the norm, those names were approximately ten-times more common on manifests from the Lower South.

Ironically (surely we can agree that this is ironic), I found the explanation I was looking for in the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database. As you can see in the graph below (on the left), and as you surely know, three-quarters of the transatlantic and intra-American trafficks of enslaved Africans to Virginia and Maryland took place prior to 1750. In fact, both Virginia and Maryland banned the trafficking of captive Africans from foreign shores prior to the federal ban of 1808; Virginia did so in 1778, and Maryland outlawed both the international and domestic traffic of enslaved people into the state in 1783. (Given the enslaved population of the Chesapeake was largely growing as a result of natural reproduction by 1720 or 1730, enslavers in the region decided they didn’t “need” the transatlantic and intra-American trades anyway.)

Transatlantic and Intra-American traffics of enslaved Africans to Virginia and Maryland (Transatlantic Slave Trade Database).

Transatlantic and Intra-American traffics of enslaved Africans to the Lower South (Transatlantic Slave Trade Database).

The transatlantic and intra-American trafficks to the Lowcountry, in contrast, took place significantly later. In mathematical terms, whereas seventy-five percent of the transatlantic traffic to the Chesapeake took place before 1750, eighty percent of the traffic to South Carolina and Georgia took place after that date. Likewise, ninety percent of the individuals trafficked to the Lowcountry from the Caribbean and South America disembarked after 1750. What this means is that the two populations trafficked to New Orleans in the antebellum coastwise trade—the population from the Upper South and the population from the Lower South—had distinct ancestral histories in North America. Simply put, the individuals trafficked from the Chesapeake came from families that had been there for many generations—typically four, five, or even six. In contrast, those trafficked from the Lower South were mostly the relatively close descendants of survivors of the Middle Passage. Some were African-born themselves. Clearly then, last names were acquired over many generations of enslavement in the Upper South. (This also explains why surnames for enslaved persons are not common on records from the colonial era, including the one pictured in part below.)

Excerpt of an “inventory” of enslaved persons taken at the Doughoregan plantation, belonging to the Carroll family, in Howard County, MD in 1773. In 1836, Charles Carroll of Doughoregan, the grandson of the man who probably drew up this record, trafficked 51 people to New Orleans; he had leased them to a sugar plantation. The names of the 51 appear in Oceans of Kinfolk. I have been able to trace most to people listed on this document and others from the Carroll archive. For more information please see this site.

But why did the enslaved population of the Upper South gradually adopt surnames? After all, in the era of the transatlantic slave trade, mononyms were the norm in much of West Africa. The answer is clear once we notice that from the colonial period onward, enslaved people generally retained their surnames when they were sold to new enslavers. Clearly, and despite whatever enslavers told themselves and each other, enslaved people did not take up surnames to signal association with those who kept them in bondage. They took them up to signal association with their kin.

What all of this means is that when enslaved people stood before customs officials in the forty years before the Civil War and answered the question “what is your name?” with full and formal names, they were claiming dignity, yes, but they were also claiming the rites and rights of relationality, of kinship—past, present and future. You see it now, right? This was defiance. This was refusal. On the very documents designed to render them kinless, fungible units of value, enslaved people proclaimed, instead, the inalienability of blood.

By the way, this is not to say that the names listed on manifests from the Lower South—nearly all of them containing first names only—are any less significant as markers of relational identity. Those names, too, gesture toward a common ancestral history. By virtue of their Africanness (the prevalence of day and place names, for example, as well as their mononymic structure), the names on manifests from the Lower South signify an embodied proximity—of culture and of memory—to African ancestors.

Clearly, then, just as we must understand manifests themselves as tools of commodification and alienation, we must also recognize the names those documents bear as living testimonies from the enslaved themselves: contrary claims of relationality and kinship resounding still.

But when I urge you—as I will do very soon—to consider the claims emanating from these documents, I am not only referencing those claims, like the ones I just described, which were articulated by the enslaved. I am referencing, also, enslavers’ claims to property and power, and the devastation those claims wrought.

By systematically researching the names of enslavers listed on manifests, I was able to determine that approximately 85 percent of the individuals sent by sea to New Orleans from elsewhere in the United States between 1820 and 1860 were trafficked by professional traders. Given the fact that traders purchased most people singly, regardless of their family ties, this was a devastating finding. Knowing this and therefore suspecting what I would find, I nonetheless looked for evidence of the splintering of enslaved families in the data by analyzing the last names of captives on each voyage. If an individual shared a surname with no one on board, I interpreted that to mean they had been sold to the trader now trafficking them to New Orleans without kin. Likewise, if two individuals were listed sequentially on a manifest and shared a surname, I assumed they were kin. This was not a perfect method by any means, but I knew it would be right more than it would be wrong. With this method, I ultimately determined that approximately 65 percent of the individuals trafficked to New Orleans were totally separated from their entire families before the voyage even started.

Just because relatives were trafficked on the same voyage, however, did not mean I could assume those individuals were sold together in New Orleans. For this reason (and others), I also examined several thousand notarial records of the sales of enslaved people in New Orleans. Eventually, I managed to locate the sales of approximately 1,000 individuals I recognized from my dataset. Then, I designed a metric with which I could assess the certainty of each “match,” meaning the certainty that two records—a manifest and a bill of sale—referred to the same person. Doing this, I confirmed approximately 500 "matches” with certainty. Finally, then, I was able to estimate how many relatives were sold together in New Orleans, and the answer was: very, very few.

All in all, it is clear that nearly 90 percent of the individuals trafficked to New Orleans in the coastwise trade were permanently separated from every single member of their family: a spectacular and systematic assault of African American kinship with which we have not yet begun to reckon.

Excerpt of manifest of the Uncas, sailing from Alexandria to New Orleans, 1839. Note the name “Celia Ganes.”

Excerpt of manifest of the Uncas, sailing from Alexandria to New Orleans, 1836. Note the name “Moses Gaines.”

Advertisement posted by Celia Rhodes (née Gaines) in the Southwestern Christian Advocate, 1880.

This—all of this—is what I mean when I say this data cannot be understood, not fully, unless we understand its multiple meanings in relation to kinship. On the one hand, this data represents kinfolk, yes. Every single person in in Oceans of Kinfolk was somebody’s somebody. They were individuals, too, but don’t you see how thoroughly the relational and individual entwined? And whether the bearers of those names came from families enslaved in North America for generations or families just recently uprooted and rerooted in American soil, we cannot ignore the ways the names listed on each and every manifest encapsulate centuries of ancestral history. But recall, too, that these documents are Janus-faced. They are evidence of—were tools of—grotesque violence against the same kinships to which the enslaved insurgently testified. So how, then, does one do justice to all of these truths?

I thought, for a time, I could learn that from you.

I arrived at the University of California - Santa Cruz in January of 2021, having defended my dissertation less than a month prior. In fact, I left my parents’ home late on Christmas night, as soon as the festivities were over. That is how eager I was to get to California and to get to work, with you. Driving across the country, I thought about what it would mean to join you, as I soon would, as Co-Editor of a project that was not only one of the oldest digital humanities projects around, but the one that had appointed itself steward of so much of the evidence documenting the gravest crime humans have ever committed against themselves.

A month after I arrived, Jamelle Bouie published an essay in the New York Times Sunday Review about your project—which was then my project, too—and the complications of producing data about slavery and enslaved people. Jamelle conducted a formal interview with me for the piece, but the truth is we had been talking about this topic for more than a decade by then. By the time the article came out though, I had a nagging feeling that the decision to bring my work, and myself, to Slave Voyages may not have been wise. And by the time the Economist piece about Oceans of Kinfolk came out, several months later, I had developed serious concerns. In fact, while I appreciated the Economist piece for drawing attention to the most devastating truth contained in my dataset (the scale of family separations), I worried that the article was drawing attention to a project I was growing less and less proud of, at least in the state that it then existed.

You see, I came to Slave Voyages because I thought doing so was the best way to get the data I had worked so hard on and cared so much about online. “They’ve been doing this a very long time,” I thought. “It will get done the way it should.” Pretty quickly, however, I learned that the grant funding my post-doc did not actually fund the addition of my dataset, which was at its core a dataset of people, to the site. Instead, it funded the addition of my data about voyages to an existing database, the Intra-American Slave Trade Database.

But this was no problem, I was told, because another scholar, the project’s founder, was willing to integrate my data with a dataset of his own, one he would soon be adding to the site. The two datasets–African Origins and Oceans of Kinfolk–would have separate user interfaces, meaning it would appear to users that they were distinct datasets, but in the back-end of the site, it would be the same set of columns and rows. And that is what happened.

Now, I know you all think this worked out fine, but the fact is, it did not. The reason for this is that the two datasets were created from sources with very little in common. After all, the history the two datasets represented had very little in common. For example, in African Origins, “owner” referred to the owner of the ship. In my dataset, however, “owner” referred to enslavers, and as a rule (there were a few exceptions), enslavers did not own the vessels on which they transported captives. I pointed this problem out at its inception. Months later, however, I noticed it had not been rectified, and as a result, men in my dataset who were enslavers were instead listed as ship owners, which they were not. To make matters worse, when I pointed this out, again, I was scolded by Slave Voyages’s technical lead in a reply-all email for having “bad data.”

This, however, was far from the only problem (or problematic exchange) with roots in the decision—which was, it bears repeating, not my decision—to integrate my dataset into another dataset. Unfortunately, I quickly became so demoralized that I soon found myself hesitating to voice my concerns.

But let me be clear. Technical problems were not the primary reason I ultimately chose to resign from Slave Voyages and move my work elsewhere. On the contrary, I believe the technical issues were symptomatic of a much larger problem, which is that the Slave Voyages project operates as if it is accountable only to itself. It is a self-contained and insular universe.

This fact has many, many unfortunate implications, but I will highlight just one, which is the absolute failure of the Slave Voyages project to engage Descendants of the enslaved in a sustained, structured or meaningful way. At times, I have wondered if the team does not feel compelled to seek such engagement because so few of the sources used to construct the various Slave Voyages databases include the names of enslaved persons. Frankly, however, this makes no sense to me.

Isn’t the dehumanizing and anonymizing nature of the records (and thus the data, and thus the data visualizations, and thus…) all the more reason why your broader work must be reparative? You are dealing in documents of death and alienation. Does it not occur to you that you have a responsibility to work towards contrary ends?

Perhaps, however, you feel such work is not yours to do; your calling is education, not justice. The problem with this logic, I am sad to say, is that whether you intend it to or not, your work will ripple through this world in ways that are profoundly moral, ethical, and spiritual. If you choose to replicate the lies of enslavers–that humanity should have a price and that kinship is rendered null and void by the ledger book–then those are the lies that will seep not only into our world but into ourselves. If such lies are worth repeating–as evidence of harm, as genealogical signposts, as scholarly research, as whatever–then so be it. But surely we must call them what they are and state plainly why we are repeating them.

By now, I hope you are beginning to understand why I felt I had no choice but to depart from our collaboration. And this brings me, at last, to the reason I am writing to you now.

In June of 2023, I informed the Slave Voyages team of my decision to resign as Co-Editor of the project as well as from its Operational Committee. I also shared my wishes that my work be removed from the Slave Voyages website. As I explained, I was revising and improving the database and republishing it at Kinfolkology.org. As a precaution, I even trademarked the name “Oceans of Kinfolk,” intending to reserve it for the dataset I built as well as my forthcoming book. (I had no interest in establishing legal ownership of the data itself, however, because I did not and do not believe ownership is the appropriate model for data of this kind.)

Around the same time, I had the honor of Co-Founding a new project, Kinfolkology, with Eola Lewis Dance. Kinfolkology’s foundational mission is to integrate datawork related to slavery and the lives of the enslaved with justice work, including demands for reparations, and the engagement of Descendant communities: commitments informed by the conviction that Eola and I share, which is that while enslaved ancestors may no longer be living, they were and are part of communities and families that are very much alive. For this reason, we are committed to establishing a governance model for Kinfolkology that is built around the concept of structural parity, or total shared authority, with Descendants. Structural parity is also guiding our efforts to engineer a new model of data stewardship, one that honors the work of individual scholars, yes, but also the claims of living communities and families to that very same data—the claims of kinfolk.

As I am sure you recall, however, the Slave Voyages team refused to honor my request to remove my work and offered at least three reasons for this decision in writing and in the course of a virtual conversation. The first reason–offered by the Slave Voyages technical lead–was that removing my data was “too complicated,” because “there’s not a delete button.” The second reason, stated by another member of the team, was that “this data is an asset.” (While I appreciated the candor of this statement, I am mystified by it, especially considering that our conversation included an individual whose great-great-great-grandmother is very likely among those listed in Oceans of Kinfolk.) The third and final reason offered was that individuals other than myself played a role in the conversion of my data from Excel/SPSS spreadsheet to online resource.

I have nothing to say in regard to the first two arguments cited above. As to the third, I am more than happy to acknowledge its truthfulness, and I thank the relevant parties for their hard work. But let me be clear. I remain and will ever remain unmoved.

By refusing to remove my work, you are violating widely accepted norms related to data consent and scholarly collaboration. Far more importantly, to me at least, you are refusing to heed the clear calls emanating from this data to acknowledge and engage kin and community. I call upon you to listen instead.

Do not think, however, that just because I have spent these many pages laying out for you the irrefutable demands of the dead to engage with the living that resound in my spreadsheets, there is no call issuing forth from yours. The call is there. I cannot tell you why you do not hear it but I promise you, it is there. Listen for it. Listen for it in your bloodless data visualizations. Listen for it in your imputed death ratios. Listen for it in the silence of 12.5 million names. And if, after all that, you still hear nothing at all, I ask you: What right do you have to do this work?

Sincerely,

Jennie K. Williams

Former Co-Editor, Slave Voyages

Co-Founder, Kinfolkology

Author, Oceans of Kinfolk